Module 0903

Like dissolves like? Shades of grey

Are all polar liquids miscible with all polar liquids?

Are all non-polar liquids miscible with all non-polar liquids?

Are all polar liquids immiscible with all non-polar liquids?

Must it be all-or-nothing? Partial miscibility?

Things (miscibilities) are not as clear-cut as the saying "like dissolves like" suggests ....

Prof Bob clarifies the non-universality of the saying "Like dissolves like"

KEY IDEAS - Like dissolves like? Shades of grey

There is a commonly used principle for predicting the miscibility of molecular liquids in each other: “Like dissolves like”.

More specific statements of this generalization are:

Water and ethanol are miscible. This observation is consistent with the first category above

More specific statements of this generalization are:

- Substances whose molecules are polar are miscible with other substances whose molecules are polar

- Substances whose molecules are non-polar are miscible with other substances whose molecules are non-polar

- Substances whose molecules are non-polar are not miscible with substances whose molecules are polar.

Water and ethanol are miscible. This observation is consistent with the first category above

Mixtures of water and some alcohols

Water and ethanol are miscible. This observation is consistent with the first category above (polar liquids and polar liquids)

Let’s consider the miscibility in water of some other alcohols with just one O-H group. We’ll focus on the number of carbon atoms in the chain attached to the –O-H group.

1-propanol [C-C-C-O-H, not showing the H atoms on the C atoms] Its molecules have a polar group. And indeed it IS miscible with water. Did you predict that, using “like dissolves like”?

1-octanol [C-C-C-C-C-C-C-C-O-H] Its molecules have a polar group. But it is NOT miscible with water. If we shake up some octanol and water, it will remain as two layers – the less dense octanol being the upper layer. Did you predict that?

Unthinking use of the saying “Like dissolves like” leads us to the wrong prediction. Furthermore, it give us no basis for understanding why 1-octanol and water are immiscible.

To make sense of this observation, we can use the more rational approach based on the two different driving forces of entropy and energy discussed in Module 0902: Miscibility of liquids in each other.

This approach uses Prof Bob’s law of miscibility of liquids in each other, which views miscibility/immiscibility as the result of a competition between the "driving forces" of increase of entropy and decrease of energy. There is a natural tendency for the molecules of different liquids to intermix among each other (entropy factor) unless there are energy requirements preventing them from doing so.

This approach uses Prof Bob’s law of miscibility of liquids in each other, which views miscibility/immiscibility as the result of a competition between the "driving forces" of increase of entropy and decrease of energy. There is a natural tendency for the molecules of different liquids to intermix among each other (entropy factor) unless there are energy requirements preventing them from doing so.

For example, in the case of 1-propanol and water, which are miscible, the net energy requirement is the result of

This approach allows us to explain observed miscibilities, rather than to predict.

For example, the observation of propanol-water miscibility tells us that even if the net energy demand is unfavourable to mixing, it is not enough to cancel out the natural tendency to mix.

- the energy needed to separate the water molecules (A strong network of hydrogen bonding between water molecules).

- the energy needed to separate the propanol molecules (Some hydrogen bonding between the molecules because of the highly polar O-H group in each molecule).

- compensation of energy due to attractions between propanol molecules and water molecules if they are dispersed among each other.

This approach allows us to explain observed miscibilities, rather than to predict.

For example, the observation of propanol-water miscibility tells us that even if the net energy demand is unfavourable to mixing, it is not enough to cancel out the natural tendency to mix.

How can we make sense of that? We can imagine that a large factor in the energy demand is due to the fact that if the octanol and water molecules to disperse among each other, the long C-C-C-C-C-C-C-C- chain of each octanol molecule will need to push apart several water molecules from each other – against the strong forces of attraction due to hydrogen bonding.

This requires so much work to be done (energy to be input) that it is not sufficiently compensated by interactions between octanol and water molecules to allow scrambling.

This requires so much work to be done (energy to be input) that it is not sufficiently compensated by interactions between octanol and water molecules to allow scrambling.

Miscibility in all proportions

If we shake up some 1-propanol and water together, regardless of whether we make a mixture 99% propanol, or only 1% propanol, it remains as only one layer – a solution of these two substances in each other. They are said to be miscible in all proportions.

If we shake up some 1-propanol and water together, regardless of whether we make a mixture 99% propanol, or only 1% propanol, it remains as only one layer – a solution of these two substances in each other. They are said to be miscible in all proportions.

Immiscibility

If we shake up some 1-octanol and water together, no matter how little octanol we add to some water, nor how little water we add to some octanol, the liquids separate out into two layers (less dense octanol on top). These are immiscible.

If we shake up some 1-octanol and water together, no matter how little octanol we add to some water, nor how little water we add to some octanol, the liquids separate out into two layers (less dense octanol on top). These are immiscible.

Partial miscibility

1-propanol (with its 3-carbon atom chain) is miscible with water, but 1-octanol (8 carbon atom chain) is not. What about 1-butanol (4 C atoms), 1-pentanol (5 C atoms), 1-hexanol (6 C atoms), and 1-heptanol (7 C atoms)? There must be a switch from miscibile with water to immiscible somewhere along this series.

Suppose that we add some 1-butanol to 100 g of water.

If we add any amount of butanol up to 8g, it all dissolves, and there is only one layer. Are 1-butanol and water miscible? Wait …

Any small additional amount over 8g does not dissolve: another layer forms on top. And the more butanol that we add, the larger does the upper layer become. (Just like adding salt to water in increments – you come to a point where no more can dissolve - a saturated solution)

So, 1-butanol is miscible with water only up to a point.

1-propanol (with its 3-carbon atom chain) is miscible with water, but 1-octanol (8 carbon atom chain) is not. What about 1-butanol (4 C atoms), 1-pentanol (5 C atoms), 1-hexanol (6 C atoms), and 1-heptanol (7 C atoms)? There must be a switch from miscibile with water to immiscible somewhere along this series.

Suppose that we add some 1-butanol to 100 g of water.

If we add any amount of butanol up to 8g, it all dissolves, and there is only one layer. Are 1-butanol and water miscible? Wait …

Any small additional amount over 8g does not dissolve: another layer forms on top. And the more butanol that we add, the larger does the upper layer become. (Just like adding salt to water in increments – you come to a point where no more can dissolve - a saturated solution)

So, 1-butanol is miscible with water only up to a point.

And what’s more, the two layers that are present beyond that point are not pure water and pure butanol: we can think of the lower layer as a solution of 1-butanol in water, and the upper layer as a solution of water in 1-butanol.

At 20 °C, the compositions of the two layers are the following:

Upper layer: 20% water, 80% butanol

Lower layer: 8 % 1-butanol, 92% water

Pairs of liquids such as 1-butanol and water are said to be partially miscible.

At 20 °C, the compositions of the two layers are the following:

Upper layer: 20% water, 80% butanol

Lower layer: 8 % 1-butanol, 92% water

Pairs of liquids such as 1-butanol and water are said to be partially miscible.

So you want to know about 1-pentanol, 1-hexanol, and 1-pentanol? You probably won’t be surprised to learn that the larger the hydrocarbon section of the molecules, the less soluble is the alcohol in water.

The solubilities at 25 °C (in mol of alcohol per L of water) of the C4 to C7 alcohols are listed here:

1-butanol 1.1

1-pentanol 0.03

1-hexanol 0.006

1 heptanol 0.0008

Butanol and pentanol can be regarded as partially miscible with water.

For all practial purposes, we would probably classify 1-heptanol as immiscible with water – although no two liquids are absolutely immiscible: there is always at least a tiny amount of A in the layer of B, and some B in the layer of A.

The solubilities at 25 °C (in mol of alcohol per L of water) of the C4 to C7 alcohols are listed here:

1-butanol 1.1

1-pentanol 0.03

1-hexanol 0.006

1 heptanol 0.0008

Butanol and pentanol can be regarded as partially miscible with water.

For all practial purposes, we would probably classify 1-heptanol as immiscible with water – although no two liquids are absolutely immiscible: there is always at least a tiny amount of A in the layer of B, and some B in the layer of A.

Solubilities in non-polar solvents.

Oppositely to the relative solubilities in water, 1-octanol is more soluble in hexane than methanol is.

And we can use that same reasoning to explain relative solubilities in non-polar solvents: We can also use Prof Bob’s law of solubilities of molecular liquids in each other to make sense of such observations.

Oppositely to the relative solubilities in water, 1-octanol is more soluble in hexane than methanol is.

And we can use that same reasoning to explain relative solubilities in non-polar solvents: We can also use Prof Bob’s law of solubilities of molecular liquids in each other to make sense of such observations.

Aha!

We may not be able to predict miscibilities with certainty, but we can make sense of observations sensibly.

We may not be able to predict miscibilities with certainty, but we can make sense of observations sensibly.

SELF CHECK: Some thinking tasks

1. 1-Octanol is immiscible with water, but miscible with hexane. Which of the following is/are correct in relation to the immiscibility of 1-octanol with water?

A 1-octanol molecules are polar, and so are water molecules, so this observation is consistent with the “Like dissolves like” rule.

B There is a natural tendency (increase of entropy) for 1-octanol molecules and hexane molecules to disperse among each other, but the net energy demand of doing so is large enough to prevent this from happening.

C There is only one hydrogen bond in 1-octanol.

D The reason why the net energy demand of scrambling 1-octanol and water molecules among each other is so high is that the long 1-octanol molecules would separate a lot of water molecules from each other against the strong forces of attraction (hydrogen bonding) between them, without much compensation of energy from forces of attraction between 1-octanol molecules and water molecules.

A 1-octanol molecules are polar, and so are water molecules, so this observation is consistent with the “Like dissolves like” rule.

B There is a natural tendency (increase of entropy) for 1-octanol molecules and hexane molecules to disperse among each other, but the net energy demand of doing so is large enough to prevent this from happening.

C There is only one hydrogen bond in 1-octanol.

D The reason why the net energy demand of scrambling 1-octanol and water molecules among each other is so high is that the long 1-octanol molecules would separate a lot of water molecules from each other against the strong forces of attraction (hydrogen bonding) between them, without much compensation of energy from forces of attraction between 1-octanol molecules and water molecules.

2. 1-Octanol is immiscible with water, but miscible with hexane. Which of the following is/are correct in relation to the miscibility of 1-octanol with hexane?

A 1-octanol molecules are polar, but hexane molecules are not, so this observation is not consistent with the “Like dissolves like” rule.

B There is a natural tendency (increase of entropy) for 1-octanol molecules and hexane molecules to disperse among each other, and the net energy demand of doing so is not too large to prevent this from happening.

C The reason why the net energy demand of scrambling 1-octanol and hexane molecules among each other is not too high is that (i) although a lot of energy is need to separate 1-octanol molecules from each other during scrambling, and (ii) a lot of energy is needed to separate hexane molecules from each other during scrambling, (iii) there is large energy compensation due to the strong forces of attraction between 1-octanol molecules and hexane molecules when dispersed among each other.

D The reason why the net energy demand of scrambling 1-octanol and hexane molecules among each other is not too high is that (i) not a lot of energy is need to separate 1-octanol molecules from each other during scrambling, and (ii) not a lot of energy is needed to separate hexane molecules from each other during scrambling, (iii) the energy compensation due to the dispersion forces of attraction between 1-octanol molecules and hexane molecules when dispersed among each other is similar to the energy requirements of (i) and (ii).

A 1-octanol molecules are polar, but hexane molecules are not, so this observation is not consistent with the “Like dissolves like” rule.

B There is a natural tendency (increase of entropy) for 1-octanol molecules and hexane molecules to disperse among each other, and the net energy demand of doing so is not too large to prevent this from happening.

C The reason why the net energy demand of scrambling 1-octanol and hexane molecules among each other is not too high is that (i) although a lot of energy is need to separate 1-octanol molecules from each other during scrambling, and (ii) a lot of energy is needed to separate hexane molecules from each other during scrambling, (iii) there is large energy compensation due to the strong forces of attraction between 1-octanol molecules and hexane molecules when dispersed among each other.

D The reason why the net energy demand of scrambling 1-octanol and hexane molecules among each other is not too high is that (i) not a lot of energy is need to separate 1-octanol molecules from each other during scrambling, and (ii) not a lot of energy is needed to separate hexane molecules from each other during scrambling, (iii) the energy compensation due to the dispersion forces of attraction between 1-octanol molecules and hexane molecules when dispersed among each other is similar to the energy requirements of (i) and (ii).

3. Which of the following do you think is/are correct?

A Acetic acid is miscible with water, consistent with the “Like dissolves like” principle.

B Decanoic acid is miscible with water, consistent with the “Like dissolves like” principle.

C Decanoic acid is immiscible with water, consistent with the “Like dissolves like” principle.

D Decanoic acid is immiscible with water, inconsistent with the “Like dissolves like” principle.

A Acetic acid is miscible with water, consistent with the “Like dissolves like” principle.

B Decanoic acid is miscible with water, consistent with the “Like dissolves like” principle.

C Decanoic acid is immiscible with water, consistent with the “Like dissolves like” principle.

D Decanoic acid is immiscible with water, inconsistent with the “Like dissolves like” principle.

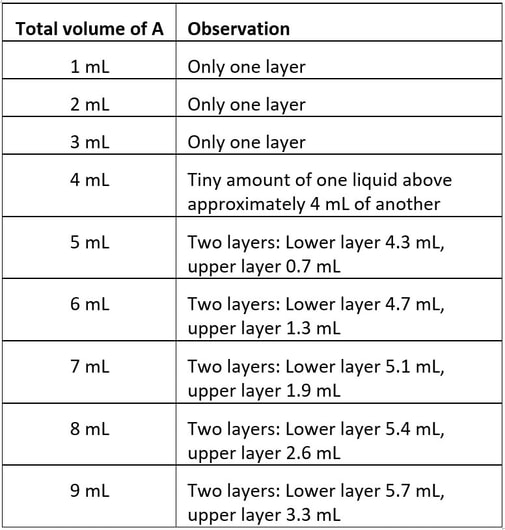

4. Liquid A is added incrementally to 10 mL of liquid B. Here are the experimental observations, after shaking on each addition:

Which of the following is correct?

A A and B are miscible in all proportions.

B A and B are immiscible.

C (i) A and B are partially miscible, (ii) after addition of 4 mL of A, the two layers are pure A and pure B, and (iii) A is less dense than B.

D (i) A and B are partially miscible, (ii) after addition of 4 mL of A, the two layers are pure A and pure B, and (iii) A is more dense than B.

E (i) A and B are partially miscible, (ii) after addition of 4 mL of A, the the lower layer is a solution of A in B, and the upper layer is a solution of B dissolved in A, (iii) A is less dense than B

Answers

1. B and D

2. A, B, D

3. A and D

4. E

1. B and D

2. A, B, D

3. A and D

4. E

Finding your way around .....

You can browse or search the Aha! Learning chemistry website in the following ways:

You can browse or search the Aha! Learning chemistry website in the following ways:

- Use the drop-down menus from the buttons at the top of each page to browse the modules chapter-by-chapter.

- Click to go to the TABLE OF CONTENTS (also from the NAVIGATION button) to see all available chapters and modules in numbered sequence.

- Click to go to the ALPHABETICAL INDEX. (also from the NAVIGATION button).

- Enter a word or phrase in the Search box at the top of each page.